By: Mary Broadway, Veronica Biolcati, Ken Sutherland, Francesca Casadio, Emeline Pouyet, Agnese Babini, Gianluca Pastorelli, Danielle Duggins, Mare Walton.

Presented By: Veronica Biolcati

This presentation was given at the 46th AIC Annual Meeting, Houston, TX, in 2018. I have decided to publish this post because annual meeting blog posts were not possible last year due to the transition of the AIC blog to the current online platform. The information below is gathered from my conference notes, the BPG Annual Vol. 37 abstract, and the exhibition catalogue John Singer Sargent & Chicago’s Gilded Age in Chapter 5, “Mastery of Materials, Sargent’s Watercolors at the Art Institute of Chicago” (pgs 183-201).

The multidisciplinary efforts of Biolcati and her colleagues has provided new insights into the materials and techniques of John Singer Sargent’s works in watercolors. They have scientific evidence of artist materials used by Sargent that supports what has been understood about his works in existing research and primary sources. The new discoveries came out of research supporting the John Singer Sargent & Chicago’s Gilded Age exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago’s (AIC) in July 1, 2018 to September 30, 2018. Eleven Sargent watercolors in the AIC collection were examined with art historical research, visual observation, and scientific analysis including the use of Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometery (GC-MS), Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS), and X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) mapping, hyperspectral imaging, and macro-XRF mapping. The information gathered from the eleven watercolors has revealed Sargent’s mastery of the medium, his selection of specific pigments, and his experimentation with materials to produce certain effects in his watercolors.

The survey conducted by the AIC conservation department of more than 300 of Sargent’s watercolors in three institutions, including the AIC, found that Sargent preferred watercolor papers with a ROUGH finish. Two types of watermarks were recorded: 21 works were on J. Whatman papers, known for their highest quality, and 1 work was on “UNBLEACHED ARNOLD” paper by Arnold & Foster Ltd and the O.W paper and Arts Company. Watercolors without watermarks are visually identical to those with J. Whatman papers and are likely the same kind of papers. Based on the sizes of the watercolors in the survey, Sargent preferred using blocks of watercolor papers. This makes sense as it would accommodate his preference for working en plein air. This could be why very few watermarks are present in his watercolors because the edges of the sheets would have been trimmed by the stationer or colormen as they created the block of papers. It also appears that Sargent asked for custom sized blocks to be made for him. Sargent was deliberate in choosing the best quality materials available, and had the funds to do so. The best quality watercolor papers allowed Sargent to use his techniques like working wet in wet, scraping and blotting, and working in plein air, and ensured better stability of the pieces over time. Based on the contents of the artist's studio after his death, Sargent used materials from James Newman, Winsor & Newton, Weber, Hatfield, and Schmincke Horadam. The mix of material suppliers reflects Sargent's travels. It is also known that during his time in London, he also used materials from Charles Roberson & Co., Lechertier, Barbe & Co.

Eleven watercolors at the AIC were examined with technical analysis. While a small cross section of his works, they span 40 years and provide a good record of Sargent’s development of technique and use of materials. Pigment analysis of Girl in Spanish Costume completed in his early period (1879/80) shows a limited pallet that correlates with the watercolor sets commonly sold at the time. The contents of Sargent’s watercolor palette expands as time goes on with more expensive colors like Cadmium yellows and oranges. The pigments found in the eleven watercolors shows a consistent use of Prussian, cobalt, ultramarine, vermilion, iron oxide, organic reds, umber, chromium-based green estimated to be viridian, cadmium yellows, chromium-based yellows, and zinc white. Some of the outlier pigments found in small accents of the watercolors include red lead, Indian yellow, and emerald green. A list of the pigments found during the analysis is in Figure 1. Sargent worked mainly with pigments of good light fastness with the exceptions of some organic reds and yellows. The organic reds are particularly problematic because of how he used them, causing a shift in color or vibrancy over time in his watercolors. The AIC was surprised to find the presence of Indian yellow in one watercolor, The Patio, Vizcaya (1917), because the production of this pigment was banned in 1908. It was surmised that Sargent had a tube of this pigment acquired before its ban laying around the studio that he happened to use in this watercolor.

Figure 1. Suggested pigments used in the 11 Sargent watercolors at the AIC gathered from technical analysis.

Figure 1. Suggested pigments used in the 11 Sargent watercolors at the AIC gathered from technical analysis.

Figure 2. Sargent's Use of reds in Girl in Spanish Costume.

Figure 2. Sargent's Use of reds in Girl in Spanish Costume.

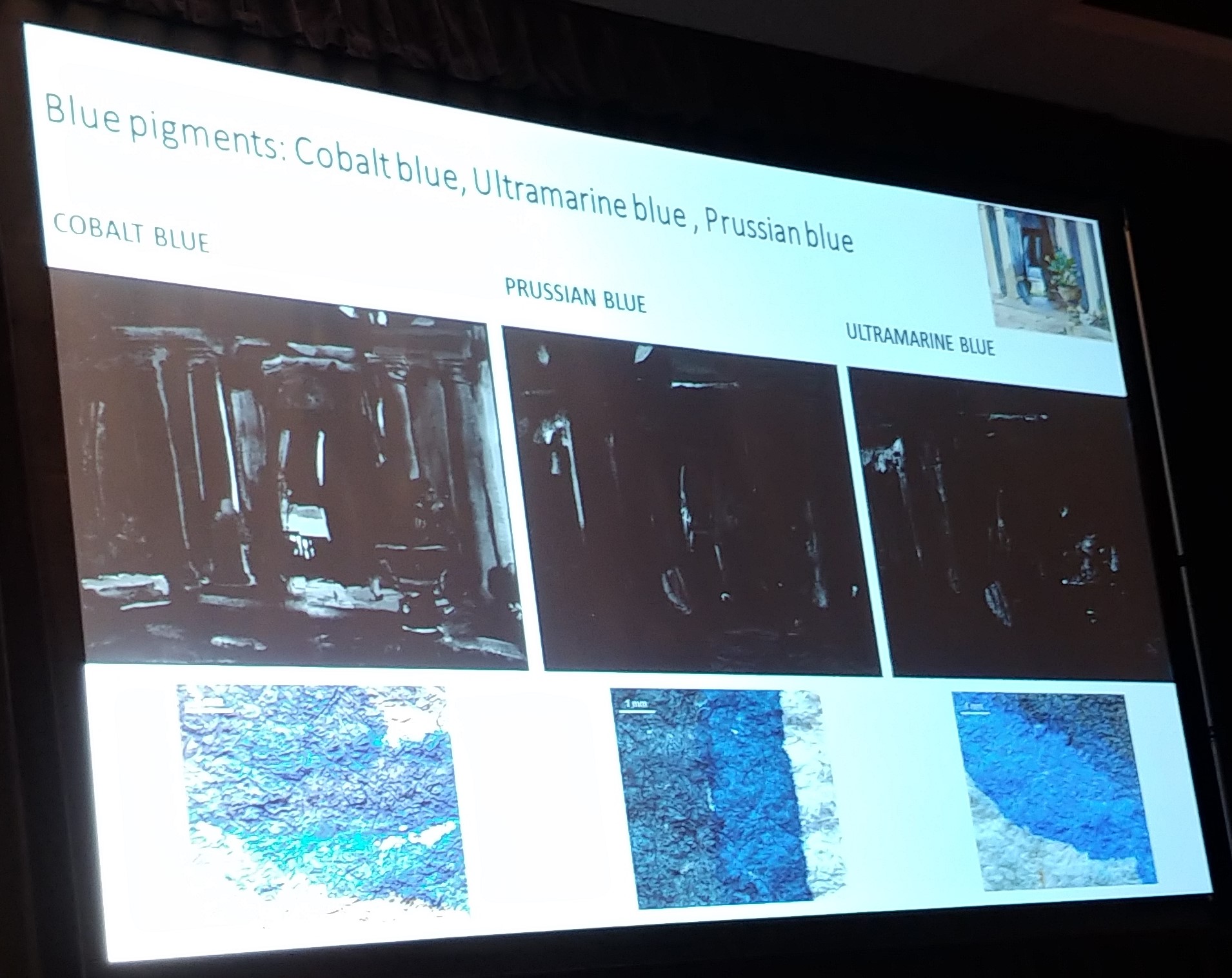

Mapping of the pigments in the watercolors gives us a glimpse into how Sargent worked with color. The exhibition catalogue describes the mapping of colors in Girl in Spanish Costume. He used red lakes in diluted and concentrated passes next to highlights of vermilion red sometimes mixed with yellow and red ochres (Figure 2). He used cobalt blue and Prussian blue for warmer or cooler shadow tones then sometimes mixed cobalt with Prussian blue and brown to create a very dark, almost black color. Another example of Sargent using visual properties of colors to create his scenes is shown in the Figure 3 from a detail of The Patio, Vizcaya where Sargent applied three different blues. The first image on the slide is mapping the application of cobalt blue. You see that the highlights in The Patio, Vizcaya in this particular detail of the work has been rendered with cobalt blue, and reads almost like a black and white image of the painting, even though it is not. The darker shadows of the detail are expressed with Prussian blue a more green blue, and accents of the more red-blue ultramarine expresses the color of the object such as the curtain or details of the planter. Sargent uses the constant play of color mixing to create cool and warm tones strategically placed to get the fabulous representation of light and form in his watercolors.

Figure 3. Mapping of blue pigments from details of The Patio, Vizcaya

Figure 3. Mapping of blue pigments from details of The Patio, Vizcaya

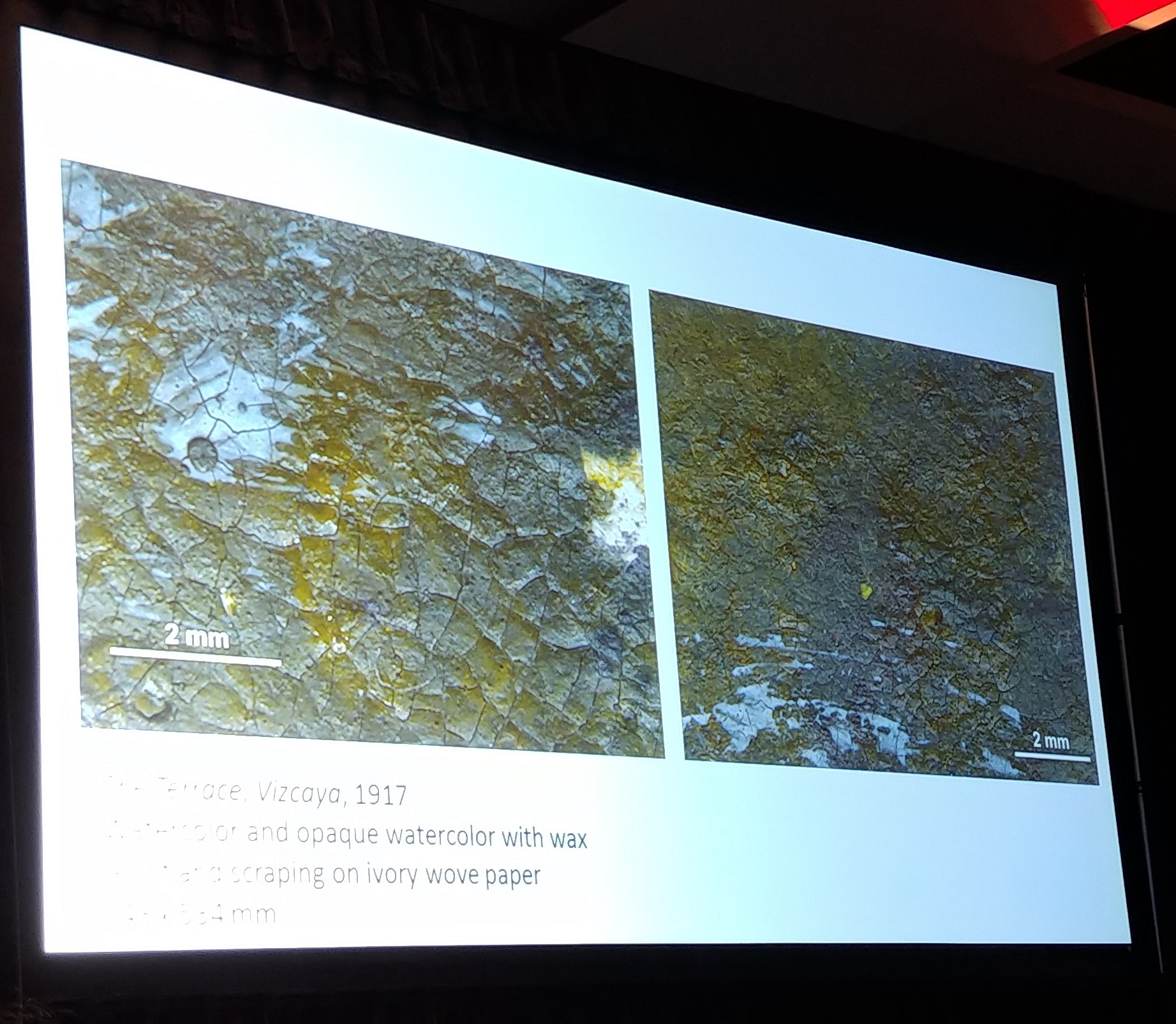

Biolcati also shared their findings that exhibit Sargent’s propensity for experimentation within the medium. His watercolors have passages of saturated glossy pigments and areas of texture. Testing of textured areas found spermaceti wax (see Figure 4). Further investigation revealed that Sargent used the wax as a crayon to create glossy highlights. Using spermaceti was a deliberate choice because of its working properties at room temperature. He used clear and white crayons applied expressively in a positive application as opposed to the negative application of a wax resist to capture the subtle effects of light. It also is apparent that Sargent mixed gum water made from gum arabic to his pigments to get a more saturated glossy finish in areas of a composition.

Figure 4. Detail of spermaceti wax media applied to watercolors.

Figure 4. Detail of spermaceti wax media applied to watercolors.

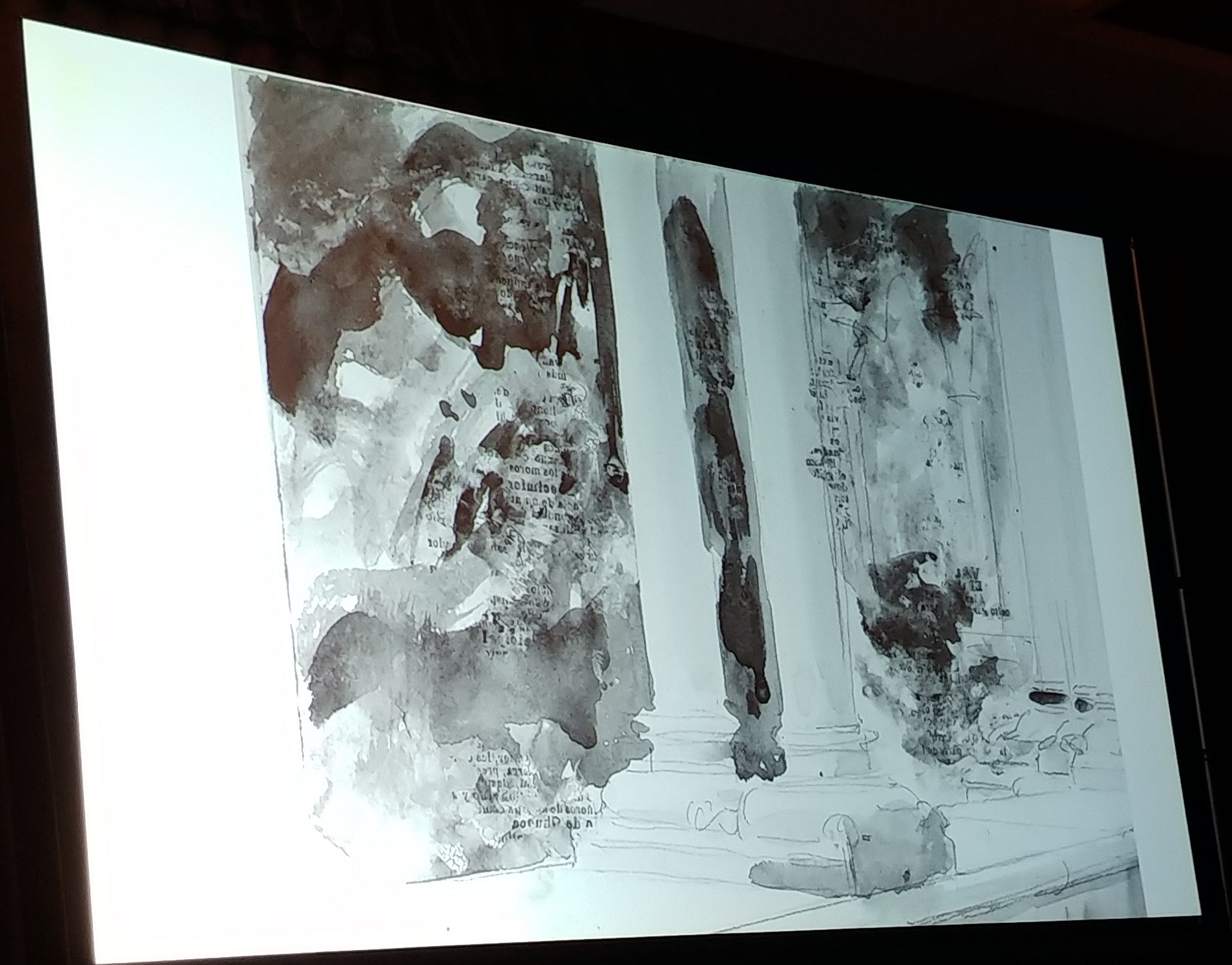

A homemade resist was also discovered. It was composed of lead white, a drying oil, mastic, and copal resins. These pieces of resist looked like small, raised white flakes. A similar homemade resist has been identified in a piece by Winslow Homer composed of lead white, pine oil, and mastic which may indicate that this was a material and technique artists were aware of at the time. Evidence of Sargent’s practice of working en plein air was found in Tarragona Terrace and Garden (c. 1908) where a Spanish newspaper was used to interleave his sketches while out in the field. As a result printing media and paper fibers were captured in the still wet zinc white highlights (Figure 5). The printing ink and paper fibers have been embedded in the areas of opaque zinc white watercolor. Over time, these residues have darkened with age altering the appearance of the work.

Figure 5. Infrared photograph of newspaper fragments found trapped in the zinc white highlights of Tarragona Terrace and Garden.

Figure 5. Infrared photograph of newspaper fragments found trapped in the zinc white highlights of Tarragona Terrace and Garden.

Sargent made use of graphite underdrawings in his watercolor sketches but the degree of detail of the underdrawings varied depending on the scene. One thing that is particularly striking about Sargent's watercolors is his ability to work with the paper and save so much of the white space of the paper to act as the highlights in his composition. This is quite difficult to do because watercolors are hard to control. Sargent’s ability to keep the white of his paper present through his painting process shows a true mastery of the medium. There is a quote in the exhibition catalogue from one of his students that captures this challenge, “He took more trouble to keep the unworried look for a fresh sketch than many a painter puts upon his whole canvas.” Biolcati and her colleagues, a team of conservators, curators, and scientists, have brought fresh information about Sargent’s work through their careful examination and scholarly research. Their findings support what has been written in the primary and secondary sources regarding Sargent’s methods and materials. His beautiful works in watercolor are the result of an artist with complete mastery of the medium expressing his artistic genius.

The information for this post came from the following sources:

- The 46th AIC Annual Meeting presentation given by Veronica Biolcati: John Singer Sargent: New Insights Into His Watercolor Materials and Techniques.

- The exhibition catalogue: John Singer Sargent & Chicago’s Gilded Age, specifically chapter 5 “Mastery of Materials: Sargent’s Watercolors at the Art Institute of Chicago” (pgs 183-201) by Mary Broadway, Ken Sutherland, Veronica Biolcati, and Francesca Casadio.

- The BPG Annual Vol. 37, 2018 abstract: John Singer Sargent: New Insights Into His Watercolor Materials and Techniques by Mary Broadway, Veronica Biolcati, Ken Sutherland, Francesca Casadio, Emeline Pouyet, Agnese Babini, Gianluca Pastorelli, Danielle Duggins, and Marc Walton.

#46thAnnualMeeting(Houston)#45th Annual Meeting (Chicago)

#bookandpaperconservation#Featured