With generous funding from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation (administered by the Foundation for the American Institute of Conservation) and the AIC Electronic Media Group, I was able to attend the American Institute of Conservation’s 2018 Annual Meeting in Houston, Texas. In this short blog post I will briefly summarise some of my personal highlights and reflect on the themes that stood out to me as a digital conservator.

The conference opened with a General Session, of which matters relating to ephemeral and digital materials were a significant part — which I am told represents an exciting first for the Annual Meeting. First up was Glenn Wharton, who discussed the important contribution of conservation theory in navigating the complex material and conceptual concerns involved in caring for contemporary art. Having spent the last few years of my life deeply immersed in theoretical aspects of conservation during my PhD research, and I wholeheartedly agree that theory has an important place in the conservation landscape.

Glenn Wharton presenting his keynote, “Materiality & Immateriality in the Conservation of Contemporary Art” in the Opening General Session.

Later, Crystal Sanchez and Lauren Sorenson continued the thread of dualistic material-immaterial concerns, this time in relation to digital storage. Presenting a ‘state of the art’ in digital storage, they also gave a timely reminder that all digital materials, while superficially intangible, are in fact rooted in the physical. Although less immediately relevant to my own work, it was interesting to hear Carrie McNeal’s presentation in the General Session, which suggested that we might consider capturing a material culture of conservation as a practice. As a digital conservator, this raised a host of questions about what the material and immaterial traces of my work might be where my interaction with artworks is largely computer-mediated.

For the remainder of the conference, I primarily attended the Electronic Media Group sessions. I was excited to find a significant number of talks were on topics relating to software preservation this year — this being my own specialisation and something I hoped to be able to discuss at the meeting. Sophie Bunz, Deena Engel, Jonathan Farbowitz, Claudia Röck and Coral Salomón all presented fascinating papers on approaches to the preservation of software, computer and internet-based artworks. I don’t have enough space here to even attempt to summarise them, but hopefully they will be represented by full papers in a forthcoming EMG Review volume! My own paper also tied in with this strand of research, in which I introduced a set of approaches to the examination of software-based artworks, building on techniques from reverse engineering.

Claudia Roek, PhD candidate at the University of Amsterdam, talking about the use of sophisticated virtualisation techniques to address the preservation of software-based art during the EMG Session - techniques I will now be experimenting with in my work with Tate.

Claudia Roek, PhD candidate at the University of Amsterdam, talking about the use of sophisticated virtualisation techniques to address the preservation of software-based art during the EMG Session - techniques I will now be experimenting with in my work with Tate.

The papers presented by Jonathan Farbowitz and Claudia Röck both touched on disk imaging to some extent, a technique which seemed to be of general interest within the EMG sessions this year. It’s interesting to see how disk imaging as a means of achieving bit-level preservation (and using forensic methods to ensure this) has worked its way into mainstream conservation practice for time-based media. The prevalence of software-based art within the EMG programme this year contributed to the feeling that methods for its conservation are becoming ever more developed, and that we might be at a point where community driven formalisation of workflows might begin to happen. This feels like an important time to be sharing knowledge and hopefully the connections that emerged from the Annual Meeting will support this kind of collaborative work over the coming years. Information sharing platforms such as the Electronic Media Group’s Wiki could be a good place to start.

A number of papers report on developing approaches to handling time-based media artworks at scale, with Eddy Colloton, Jonathan Farbowitz and Mona Jimenez all discussing their experiences of surveying and archiving large collections. It sounds like this kind of work could also be of value to institutions getting started with time-based media conservation, such as those represented in the panel discussion on Day 2.

Participants in the Saturday morning panel (from L-R: Elise Tanner, Erin Lee, Asti Sherring, Yu-Hsien Chen, Jo Ana Morfin and Alexandra Nichols), during which we heard time-based media conservation stories from three continents and five collecting organisations.

Participants in the Saturday morning panel (from L-R: Elise Tanner, Erin Lee, Asti Sherring, Yu-Hsien Chen, Jo Ana Morfin and Alexandra Nichols), during which we heard time-based media conservation stories from three continents and five collecting organisations.

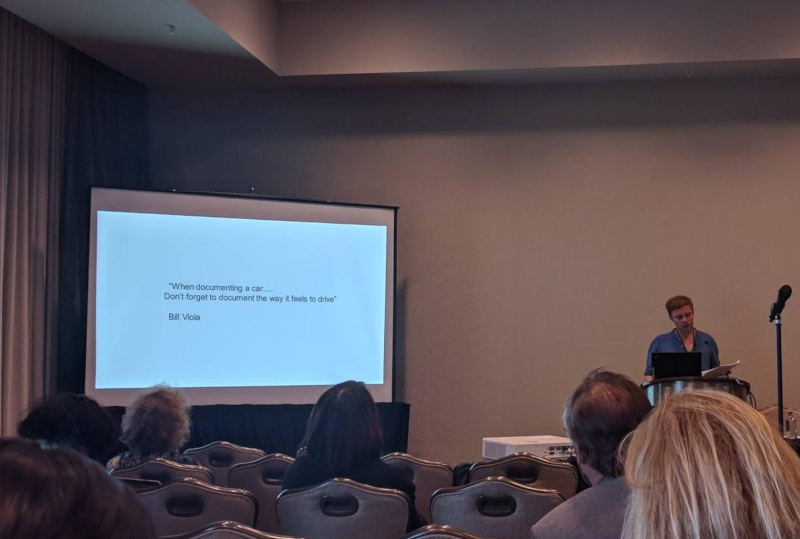

Another notable theme seemed to be work in advancing the documentation of time-based media installations. Amy Brost and Jack McConchie both focused in on the challenges of capturing meaningful documentation of installations of complex works, that might be uniquely experienced by each visitor. It was also interesting to later hear Alexandra Nichols speak on a similar topic from a different angle, as she described the process of retroactively creating documentation for poorly documented past installations. Jack’s research, which focused on virtual reality (VR) as a documentation tool, has now fed into an ongoing research project at Tate which seeks to explore how virtual reality artworks might themselves be preserved.

Jack McConchie, Time-based Media Conservator at Tate, discussing his work in the documentation of installations using VR technologies.

Jack McConchie, Time-based Media Conservator at Tate, discussing his work in the documentation of installations using VR technologies.

Briefly jumping over into the Material Transfers & Translations session towards the end of the Meeting, we heard from the Whitney’s Replication Committee on their recent work to refine the procedures governing the changes experienced by artworks in their collection. This included discussion of the hybrid approach to versioning and dating demanded by time-based media artworks, and also touched on versioning of software-based artworks — an area in the conservation of software-based art which could be a great opportunity for further research.

Ending this report on a more personal note, my experiences at the AIC Annual Meeting 2018 were really positive — both in terms of the opportunity to exchange knowledge with others working in the field and to extend my own understanding of conservation theory and practice. In the research that I heard presented at the Meeting, it is clearer to me than ever that diversity in artistic practice so yields a diversity in conservation demands and considerations. Learning more of others research is one very important way to help prepare for new challenges. In the interest of sharing more widely, I live tweeted much of the event from my Twitter handle @Tom_Ensom (I have gathered together those Tweets in a Twitter ‘Moment’ collection) as one means of involving those not physically present at the conference.

#ElectronicMediaGroup#Featured#46thAnnualMeeting(Houston)